China and Bordeaux: how the wine bubble burst

On Suzanne Mustacich’s Thirsty Dragon China’s Lust for Bordeaux and the Threat to the World’s Best Wines

29 January 2016

Book review by Panos Kakaviatos for wine-chronicles.com

I recall enjoying a 1982 and a 2003 Leoville Poyferre at the lovely Saint Julien restaurant with chateau owner Didier Cuvelier and a Chinese merchant back in April 2010. A heady time it was, as wealthy Chinese buyers – backed by the government – drove prices of elite Bordeaux chateaux to the stratosphere. Over that lunch, Cuvelier told me that “Bordeaux should enjoy the good times while it can, because history shows that market upswings are always followed by downswings.” How true.

Readers who have followed China and the wine trade no doubt already know about the infamous Chinese Bordeaux bubble bursting, tales of (still) unsold stocks of 2010 wines in negociant storage, how a Chinese ban on high-end alcohol for government officials and state-owned firms took the wind out of China’s Bordeaux buying, a general frustration from more traditional buyers with excessively high Bordeaux pricing – and current efforts by Bordeaux to win them back.

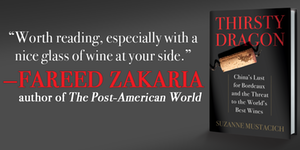

Friend and Wine Spectator Contributing Editor Suzanne Mustacich has written the definitive book on the China and Bordeaux story entitled Thirsty Dragon: China’s Lust for Bordeaux and the Threat to the World’s Best Wines, which recently won the prestigious André Simon Memorial Fund 2015 Drinks Book Award.

Well deserved recognition, as it is packed with information and reads like a page turning novel in its more or less chronological tale leading up to the market bubble bursting for high-end Bordeaux sold in China – and what lessons should be drawn as a result.

I join rather late a chorus of justified praise for this book, in time at least for winter reading. It made me think of the countless people shoveling snow from a massive storm along the eastern United States in late January 2016. But while they were putting shovels to good use, it seems that too many in Bordeaux were digging a hole in China, and should have stopped the shoveling earlier.

The hole as it turns out was Bordeaux’s “particularly disastrous handling of the en primeur system,” Mustacich concluded. And how Bordeaux chateaux which had raised prices especially egregiously “expected the negociants [middle men buyers and sellers of Bordeaux, so essential to Bordeaux sales] to absorb all of the financial shock as the demand for Bordeaux’s wines spiraled downward.”

In the tale leading to the wine trade train wreck, the reader learns much about Chinese business culture and Bordeaux trading, while understanding a growing tension between Bordeaux estates that raised prices too high, and Bordeaux negociants, who often “grumbled that the market was overheating.” The book explains how “the pendulum of power was swinging from the negociants to the estates, forcing the merchants to sit threw one obsequious lunch after another, powerless to do anything but beg for bigger allocations.”

The system worked, Mustacich explained, so long as the Chinese were willing to pay the high prices. Many deals were made in bull markets, but she quoted Vincent Yip of Topsy Trading, who already had a premonition of bad times to come: his long standing clients had stopped buying at one point in the saga, which signaled to him that the consumer market [for very high end Bordeaux] had become almost entirely made up of speculators.

“People who had bought 2010 had no confidence that the wines would hold or increase in value, and they were re-selling the wine as swiftly as they could,” Mustacich wrote.

The book includes plenty of great chapters such as “All in Name” packed with incidences of counterfeit Bordeaux – and headaches it has caused for the Chinese market: from fake wine to fake paperwork “proving” wines are genuine. The terribly frustrating practice of “brand squatting” is explained in detail with examples, such as how a wily (and crooked) Chinese sommelier student offered French companies “help” to export their wines, only to register existing brand names and thus prevent original owners from being able to profit from any sales of their… original products. Importers could not legally distribute brands registered to someone else, and what is more: other scam artists offered services for “recovering” brands, only to leave clients high and dry. Welcome to the Wild (Chinese) West.

Mustacich also reveals the crucial fact of too many Bordelais misunderstanding Chinese business culture: “Bordeaux might insist that it was unique in the wine world, but China’s central government did not care,” she wrote in the chapter “Standoff”.

Mustacich’s book also surprises many a reader. For example, clever importers would stack cheap wine around expensive Bordeaux classified growths on shipping containers to (1) insulate against extreme temperatures because they would not want to pay for the temperature controls and (2) avoid taxes because controllers would (might) only see the cheap wines on the surface.

For historical background, I never knew that Chinese vineyards in the late 19th century from The Changyu Winery had won four gold medals from the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Certainly the learning curve for wine in general has been very steep for most Chinese buyers, but readers of this book understand that China has deeper roots in viticulture than most readers think – and today there is a major effort underway for China to become the world’s largest producer of wine. There is also a serious effort by a few dedicated oenologists to find the best terroirs for fine wine made in China.

With Bordeaux facing competition in China from both home grown wine and more competitively priced foreign wines, and as China faces economic hurdles of its own these days – from a dysfunctional stock market (and debt bubble) to ever gnawing problems associated with corruption and counterfeiting – Mustacich’s book is more topical than ever.

Wine Chronicles

Wine Chronicles

Share This