English fizz hits the headlines

And it is delicious: Visit to Gusbourne Estate

By Panos Kakaviatos for wine-chronicles.com

24 July 2016

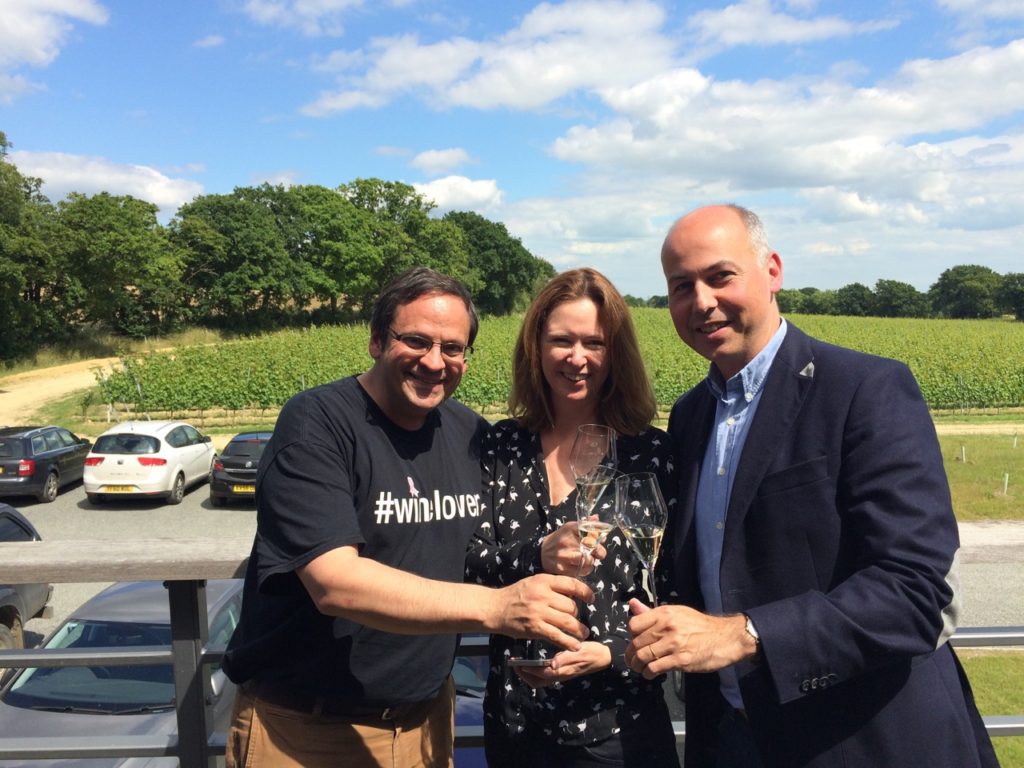

Just how delicious English bubbly can be was reconfirmed to me over dinner with Gusbourne Estate’s Andrew Weeber and promotion agency Vita Bella’s Guillaume Jourdan. It was the conclusion to a wonderful day of visiting vineyards, tasting wines, and enjoying a fine summer picnic with great wines.

We ended the visit with a relaxing summer evening, enjoying veritable fish and chips at a most charming bed and breakfast in Kent, the Woolpack Inn Warehorne.

Freshly caught cod – not fried but grilled to perfection – paired perfectly with homemade potato chips, or thickly cut fries, in American English. The wine? Gusbourne Estate 2010 Blanc de Blancs vintage brut: crisp, precise and creamy. It proved a perfect match for the food.

Made from a mixture of Burgundy and Champagne clones, whole bunch pressed in accordance with CIVC guidance, and bottled in May 2011. It had spent some three years on the lees in bottle and six months aged under cork. This was made with a whopping 9.4 grams of residual sugar per liter, but given the very low pH in England, at just over 3, a very good balance! I had tasted earlier it at the estate with fellow wine writers Adam Lechmere and Jane Anson, along with some other wines from the estate and it was the very best. And it was wonderful to see it on the wine list for dinner!

It was very sumptuous, yet precise, and showed the best balance among the others, which included the 2011 Blanc de Blancs and the 2006, 2009 and 2012 Brut Reserves. They were all good, too, but the 2010 really shined as proof positive that English bubby can be terrific.

Earlier this year, a jury of professional tasters, including French, in a blind tasting in Paris confused quality English fizz – both rosé and vintage – with high quality Champagne. Many rated the English producers higher than the French. I even did the experiment several years ago, in a blind tasting matching Taittinger NV Brut with a 2006 vintage from Breaky Bottom. Many participants, including a French wine expert, preferred the Breaky Bottom.

Buyers are noticing, too. For the first time ever, Gusbourne Estate sold to the very important U.S. market this year, just 10 years since making its first vintage, the tasty 2006.

Mainstream media, too, are paying attention. Newsweek, for example, reported in July 2016 that English sparkling wine is garnering attention for its improved quality, in part thanks to global climate change: “While overall temperatures in southern England are still slightly below those in Champagne, there is now enough annual heat to create a competitive product,” according to the report.

Indeed, “stretches of southern England can claim to possess near identical geology to France’s Champagne region, which is only a couple of hundred miles to the southeast,” according the Newsweek.

But Champagne comparisons are not so clear-cut. Champagne has a vast history and reams of reserve wines that enable millions of bottles of non-vintage bubbly, something that is not typical with English producers, who tend to release only vintages.

Sure, quality producers like Gusbourne Estate follow the Champagne method – two fermentations, the second in bottle followed by aging in bottle to maximize contact with the dead yeasts before disgorgement and adding the liqueur d’expedition. But different factors are involved when making English sparkling wine, including soils that can be different from Champagne (not all are similar to the chalky soils of Champagne), such as the sand and clays of the estate’s vineyards in Ashford. It was great to visit the vineyards in early July 2016, with Jane and Adam. Rows of vines were easy to distinguish with white roses on either end of vine rows for Chardonnay, red roses for Pinot Noir, and pink for Pinot Meunier – the three main grapes used to make Champagne.

Comparison [with Champagne] can be “superficial” explained Gusbourne Estate viticulture manager Jon Pollard. Temperatures are still colder here than in Champagne. “You can go summer camping, but when the sun goes down, it’s like turning the light switch off and you need warm clothes,” he stressed.

One main concern is elevation, explained Weeber. Gusbourne Estate vineyards range in altitude from 37 meters above sea level to zero. “Anything above 100, and you’re dead in the water,” he stressed, because it would be too cold.

A decade ago, Andrew Weeber planted the first vineyards on the finest sites of the historic Kentish farm. Weeber hails from South Africa and had a career as an orthopedic surgeon before investing in wine. His passion for wine was evident as he showed us various vineyards among the total 91 hectares that make up Gusbourne: 60 around Ashford, with sand and clay soils and 30 in West Sussex with soils of mainly flint and chalk.

In England, it is best to have vineyards that face south and southeast to ensure the warmest microclimate, Weeber added. Sunshine hours and the effect of wind to dry out rot inducing rain are important factors. In Champagne, by contrast, some vines thrive in cooler microclimates. Indeed, CIVC figures indicate a one-degree increase in temperature, overall, in Champagne over the last 30 years.

Pollard, who has been with the estate as well since 2004, at the time of the very first plantings, explained his work as we overlooked baby vines on Mill Hill, planted just in 2015, from Champagne and Burgundy clones. Pollard said sea breezes make winters less harsh and temper summer heat. De-leafing is carried out up to the harvest to maximize solar exposure for the grapes.

Later in the vat room, winemaker Charlie Holland explained that the first ever vintage, the 2006, yielded only about 8,000 Blanc de Blancs and Brut Reserve bottles. Now, however, the estate makes between 25,000 to 30,000 bottles. With vineyard expansion, it could go up to about 40,000 bottles next year, he said.

As vines get older, wine fans should expect more complexity. And there is more flexibility in making wine, making England a curious blend of New World and Old World. For one example, Champagne requires small cagettes for the harvest. But at Gusbourne, they use larger ones. “We discovered that larger ones are shaped to displace the weight evenly, which results in no crushing. Chalk one up for inflexible rules from the EU country. Just kidding.

We spoke, too, of mechanical harvesting, as mechanical harvesting machines have improved in quality, but Holland is not a fan. “We did a trial in 2013 with mechanical harvesting and it was jut too imprecise,” he said. He allowed advantages in certain situations, such as in menacing weather, when it would be better off to have something quick than nothing at all.

The bubbly scene in England is taking shape. Just over a decade ago, most producers followed a similar style, but in the last five years there have been more experiments in terms of use of oak – new or used – and varying lees aging in bottle. “It is a hugely exciting time to be here today,” said Holland, who explains that Gusbourne likes to do longer lees aging in bottle followed by cork aging afterwards than many other estates in England.

The estate counts 14 different vineyard sites, or plots, and they have different sized vats for parcel selection fermentation, using an assortment of different shapes and sizes, with 90% stainless steel.

Tasting notes (as usual, when in bold, I liked in particular; if red and bold, even more; when underlined, too, a kind of wine nirvana).

In addition to the splendid 2010, we tasted other wines, too, at the estate’s professional tasting room with a balcony overlooking the vines.

Brut Reserve 2012: Quite lean overall, but precise. About 42% Chardonnay and the rest Pinots. A cool year. “We find that cooler years are often better years for us,” explained Holland. “That may sound counter-intuitive, but we like focus.” And yes, this just released wine showed precision and pleasing raspberry fruit and citrus aspects.

Brut Reserve 2009: The weather was “unsettled” in July and August, but it was overall warmer than average, leading to higher alcohol, at 12.3%, than in 2010, which was 11.9%. The high acidity of 8 grams per liter was balanced by a whopping 10.5 grams of residual sugar. Late disgorged for England, as it had been on the lees in bottle for six years. It tastes quite deep, and comes off a bit nutty when compared to the 2012, yet offering up pleasing notes of toffee and nougat. There is a creaminess to the wine, more vinous in style, yet not quite as much verve, however, as the 2012. I could imagine this with fettuccini and shrimp or scallops in a cream sauce.

Blanc de Blancs 2011. This started out warm but then the summer turned cool. A vintage leading to 12% alcohol, with a higher pH than, say, 2010. Only four grams of residual sugar in this special cuvee (they usually have 7 to 8 grams of residual). Quite a bit of focus and energy, even steely. Holland agreed that the 2010 is more impressive: “We could have released the 2011 before the 2010,” he said.

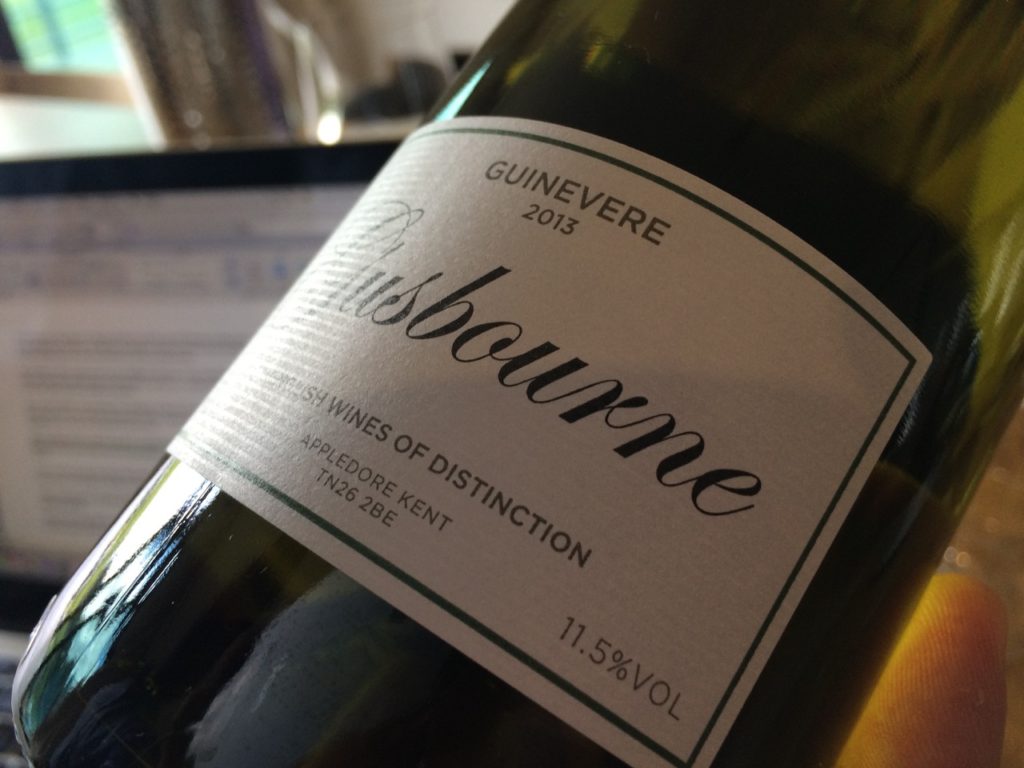

Just as impressive were two still wines that we enjoyed, produced in small quantities at the estate: a Guinevere Chardonnay from 2013 and a Pinot Noir from 2014, which I anticipated with some trepidation. But there was no reason for that. It was lovely and frank. OK, not as full bodied as a Pinot Noir from Burgundy, but not chaptalized either – only 11.5% alcohol – and showing fine richness. Interestingly the estate purchased fermenting tanks that remove the pips so that no tannin from the pips is extracted in the winemaking, thus ensuring the ripe aspect for the wine. “Our pips are really green, so we do without them,” explained Holland.

The Chardonnay, also 11.5% alcohol, is called Guinevere, named after Weeber’s daughter who has the French equivalent Genevieve. This wine was made with a bit of chaptalization and full malolactic fermentation. The team stirs the lees and use 20% new oak for aging. It was a smooth and tasty Chardonnay, that has some richness, but mainly comes across as fine Chablis. Nice job!

A fine picnic, great wines and conversation! With Andrew Weeber, Guillaume Jourdan, Jane Anson, Charlie Holland, Adam Lechmere and Jon Pollard

Finally, there was a sparkling rosé 2012 with 9 grams of residual sugar. At the tasting, I found it a bit disjointed, at first coming across as too steely, in spite of the level of residual sugar.

But then the finish was somewhat pasty and indicative of the sweetness. It was better later at a picnic we enjoyed among the vines as it paired well with some of the cheeses we had.

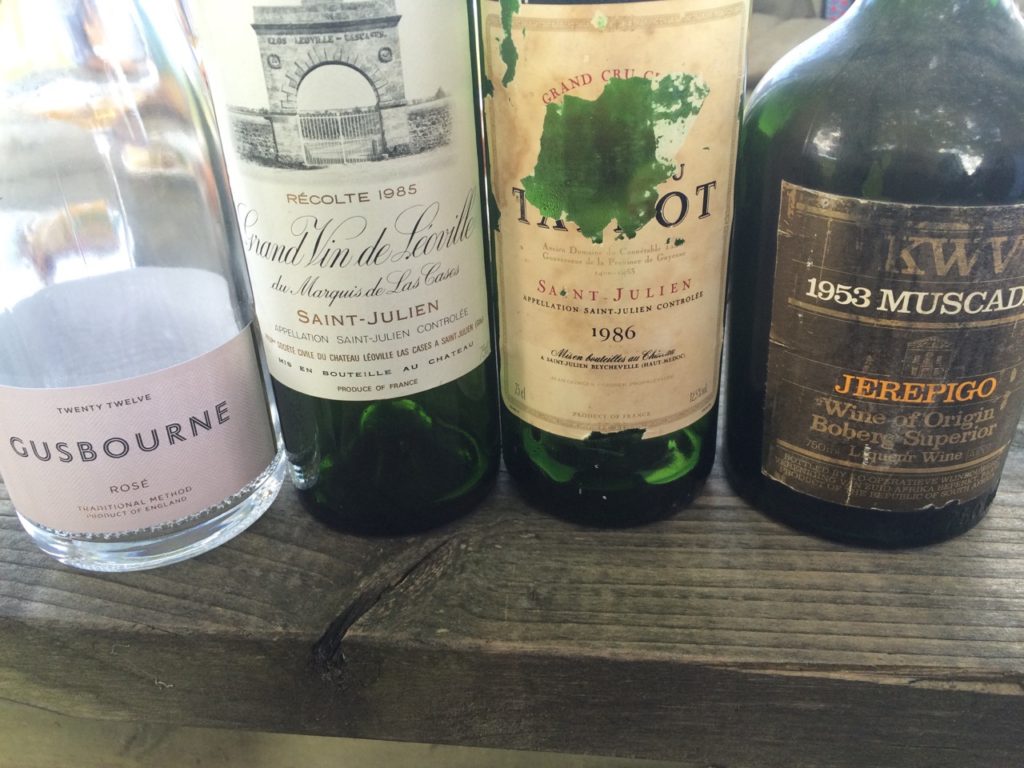

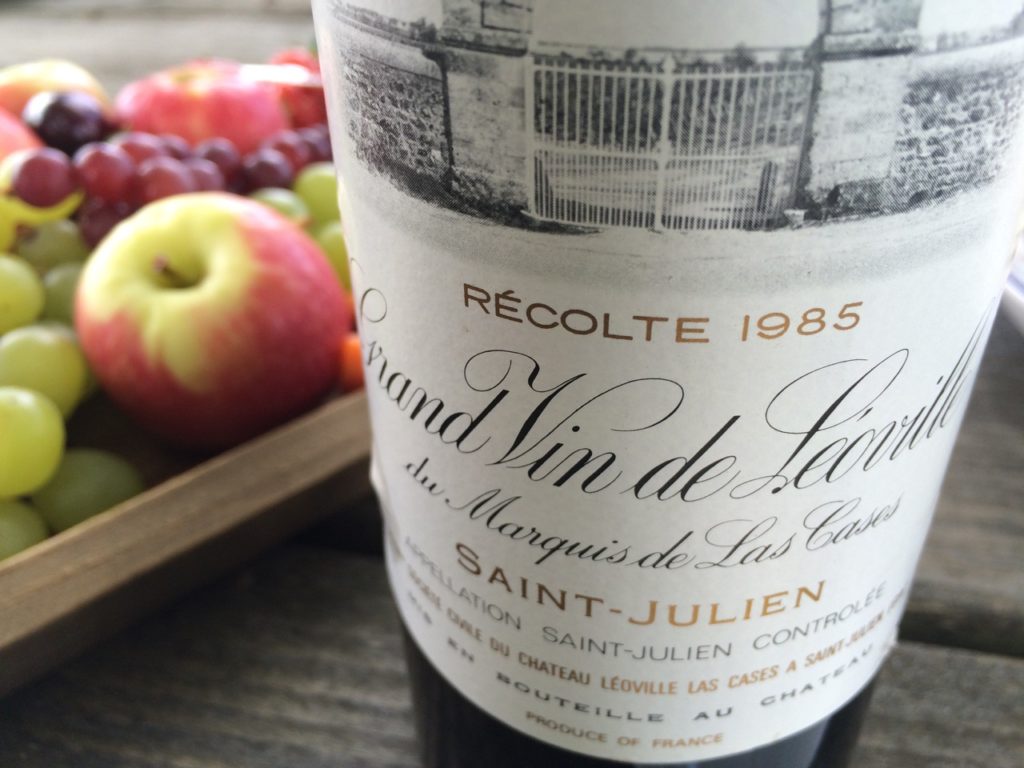

For that lunch, Jourdan generously shared an amazing Château Léoville Las Cases 1985, that was indeed very tasty, but so structured and powerful that when he served it blind, I guessed a Pauillac from 1986. Great Bordeaux. He also brought another great Bordeaux, Château Talbot 1982, that was excellent as well albeit not quite as structured and full bodied as the LLC.

Finally, Weeber brought a delectable Jerepigo Muscatel 1953 (!), a vin de liqueur from South Africa with what seemed to be at least 150 grams of residual sugar, but it had a smooth, salty freshness resembling a fine, old Sherry. We said that the world has its share of problems, Brexit among them, but all the more reason to enjoy the important things in life, like great wine and company.

See also http://adamlechmere.blogspot.fr/ and http://www.newbordeaux.com/

Wine Chronicles

Wine Chronicles

Share This