Alsace: Put dryness levels on the front label

And the grape names, too

By Panos Kakaviatos for wine-chronicles.com

30 June 2018

This may seem a bit like a rant, but I have been living the better part of the last 20 years in Alsace. And I like Alsatian wine very much. The theme of this post? Info! And with Alsace, customers want (more of) it.

The setting was the biennial Millésimes d’Alsace earlier this month.

Wine writers from all over the world trekked to Colmar to taste wines from the famous Alsace wine-growing region. Over lunch a few of us got to enjoy a lovely 2014 Riesling. We knew it was going to be dry, or at least we guessed as much. And it was: wonderfully so. The producer? Domaine Allimant-Laugner. The appellation? Alsace Grand Cru. And location? Praelatenberg. Sound German? Of course it does. The bottle looks that way, too. But more on that later, because most readers here are familiar with Alsace bottle shapes and (often) German sounding place names.

You may notice a new Alsace Wine logo in the hyperlink to the Praelatenberg Alsace Grand Cru that I included in the above paragraph. Indeed, this year’s event marked the unveiling of a new logo for the wines of Alsace in a promotional film worthy of a glitzy Champagne marketing campaign. Interspersed with high definition visuals of gorgeous vineyard slopes – accentuating Alsace’s multiple terroirs – the film featured some really nifty drone-based images. I took a short clip from that unveiling in the video below.

The new logo is appealing and simple: that is to say, an effective marketing tool. And the website sums up very nicely information about the wines, including pithy summaries for the grand cru sites. Sure, you may have not yet heard of Praelatenberg but just a visit to the website and you get a fine quote: “The panoramic viewpoints from the majestic Haut-Koenigsbourg castle overlook the sharp slopes of Praelatenberg. This rich terroir produces generous and structured wines founded on a base of intense minerality.”

And yet some confusion stubbornly hampers the image of Alsace wine.

Take for example a series of grand crus from the highly acclaimed producer Marc Kreydenweiss: grape designations were left purposefully off the label. I really loved the Wiebelsberg Grand Cru(a Riesling), for its opulence and elegance, with a finish marked by pleasing bitterness. Indeed, the new Alsace website stresses that this terroir makes mainly Riesling “svelte and refined, nestled perfectly within this large terroir curve.” The vines grow on a southeast facing steep slope of pink sandstone near the edge of the village.

But – as you cannot see in the image above – one of the grands crus we tried was actually a Pinot Gris. “Are consumers expected to know this?” mused fellow taster Christer Byklum of Norway. Especially when the grand cru with Pinot Gris – the Moenchberg – can have Riesling vines by other producers, he stressed. Indeed, as you can read from the nifty new Alsace wine website, the nearly 12 hectare marl-limestone-slate and colluvium soils of this grand cru designation host no less than three grapes: Riesling 62%, Pinot Gris 23% and Gewurztraminer 15%. If Moenchberg were exclusively Pinot Gris for all producers, I would somewhatunderstand.

But what about beginners? The names, already quite Germanic and hard to pronounce for most, are hard enough to master. Is one supposed to know that that particular grand cru from that particular producer is necessarily Pinot Gris? The producer should go back to the time when he originally included the grape on the front label, as you can see in the photo, below. In any case, I am a fan of Kreydenweiss wines. They are mainly dry and pure.

But – as the saying goes – I’m jus sayin’

If it works for Champagne, it would work for Alsace

The broader (and more important) issue is the not-so-easy-to-predict dryness levels of Alsatian wine. Some professionals say that normally dry Rieslings shouldn’t have more than four grams of residual sugar per liter to be dry, but that’s confusing, given balancing acidity. A wine could have seven grams of residual sugar with high acidity and taste drier than a comparable wine with only four grams of residual sugar, but less balancing acidity.

The essential question is “What is your overall sensation?”

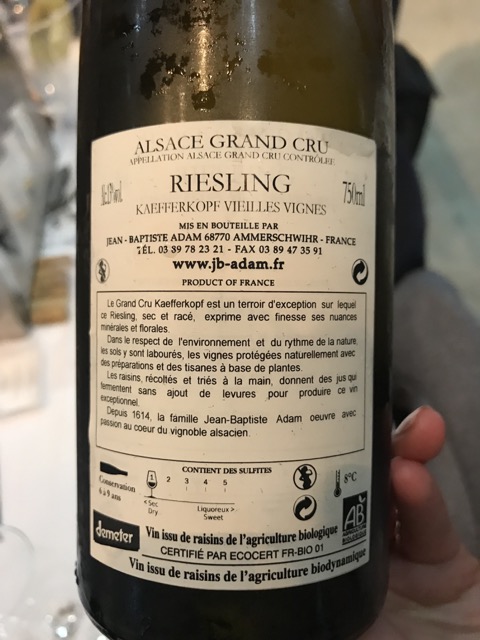

More and more producers have dry level indications on their back labels: an excellent initiative to be sure. But I think that these indications are just as important for selling Alsace wine as is showing off place names (preferably with the grapes). It is so impressive that Alsace boasts no less than 51 grand cru designations and that they soon may be complemented with yet another category of premier cru designations.

But consumers unfamiliar with many of these sometimes long words (have you ever tried the Domaine Allimant-Laugner Praelatenberg Riesling 2014?) may get stronger reassurance from the wine with front label indications of how dry the wine is.

It sure works for Champagne, and it should work fine for Alsace.

Certainly strong brands continue to sell internationally because of their brand and historic reputation. I do not think that Maison Trimbach for example is suffering in terms of sales.

It is wonderful that many in Alsace focus on place: “We should have premiers crus like the Burgundians” is an oft heard refrain. But key consumer information indicators are still missing, or at least not as clearly … indicated.

As Byklum commented, understanding the premiers and grands crus of Burgundy are relatively easy to “digest” because (a) they are all dry and (b) they leave little doubt as to the grape: either Pinot Noir or Chardonnay. Furthermore, the notion of grand cru in Alsace is a more recent thing, not having officially come into modern existence before the mid 1970s. In that sense, Alsace makes any Burgundy “minefield” seem like a picnic in the park.

Just one other item: bottle shapes resemble German wine bottles. For some consumers, this also can be confusing. Now, I would never want to change Alsace wine bottle shapes. But as Maxime Buecher of Barmes-Buecher once told me: he has an easier time selling his wine in Tokyo than he does in Paris. Partly because the names and shapes remind some French people of German wine (or outmoded impressions of … sweet German wine). So more information about dryness levels and grape varieties on the front can only help.

Of course strong brands from Alsace sell well internationally (and in France) because of their historic brand reputation, but that amounts to only a rather small percentage of… all Alsace wine production. The potential for sales for Alsace is higher because it is not being fully met.

Unbeatable price/quality ratios

OK, that was my rant … And not a particularly original one. Others would agree and have said so in various wine forums and blogs and articles already.

Why do wine lovers with an eye for quality in their wine trek to Alsace?

Because it offers some of the very best price/quality ratios for white wine in the world, period. Ironically part of this benefit can be explained by the fact that dryness levels are not as clear cut as they should be: Customers in the know find top wines for rather modest prices: from humble reserve Rieslings of no celebrated terroir to high gear grand cru designations.

In a subsequent post, I will publish tasting notes from the Millésimes d’Alsace earlier this month.

Wine Chronicles

Wine Chronicles

Very nice article and very reasonable questions. Thank you Panos Kakaviatos.