The Long Game of Greatness: Mouton Rothschild 1986

Posted on October 17, 2025

By Panos Kakaviatos for Wine Chronicles

Main photo: Chateau-Mouton-Rothschild-Cuvier-nuit-©-Pierre-Grenet-Astoria-studio.jpg

17 October 2025

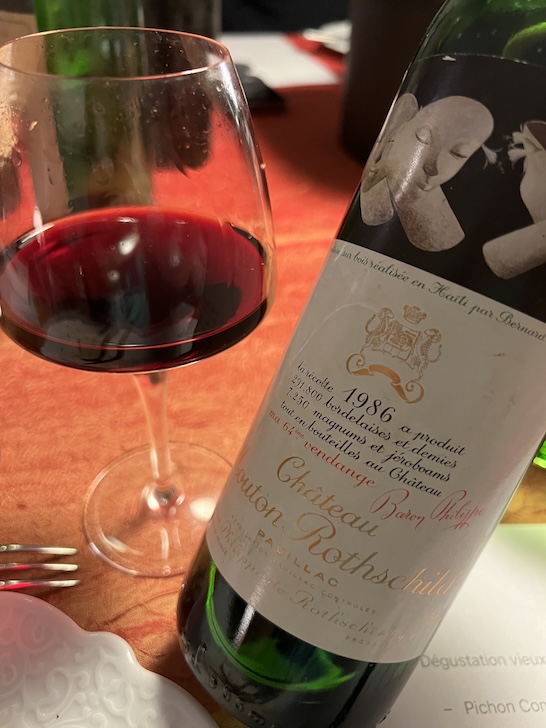

“I bought this wine upon release,” a dear friend told me, speaking about Château Mouton Rothschild 1986. “When I tried one of my bottles three years ago, it still hadn’t opened up”, he said in September 2025, nearly 40 years later.

World famous wine critic Robert Parker gave this wine from Bordeaux’s Left Bank Pauillac appellation a perfect 100 points early in its life: the same perfect score that he had given to the even more famous 1982 vintage. While the 1982 has proven more sensual and approachable, the 1986 remains indeed rather closed. But what makes the 1986 special? Why is it a legend in the making? To answer this question, let’s first examine the 1986 vintage, in general.

The 1986 growing season began slowly with a cool, damp spring, but fine weather in late spring and early summer allowed the vines to catch up. Flowering took place under ideal conditions. The summer that followed was hot, sunny, and dry, leading to drought stress. Indeed, by early September, many vines had shut down, their grapes struggling to ripen. Thanks to mid-September rains, the vines were able to “restart”. But the downpours had a negative effect for earlier-ripening Merlots, causing dilution as their thinner skins absorbed excess water. For estates that harvested too soon, Merlot-based wines often lacked concentration.

By contrast, growers on the Cabernet Sauvignon-dominated Left Bank (including venerable appellations Pauillac, Saint Estèphe, Saint Julien and Margaux) who waited benefited enormously: three weeks of hot, dry, and windy weather in late September and early October followed the rains, which allowed Cabernet Sauvignon to reach full maturity. Those with patience made structured and age-worthy wines — confirming 1986 as a great Cabernet vintage. So it comes as no suprise that the harvest at Mouton took place at such an appropriately later time, from 2-15 October.

How does Mouton 1986 taste today?

The wine itself blends 80% Cabernet Sauvignon, 10% Merlot, 8% Cabernet Franc and 2% Petit Verdot. A little more open than the firmly closed Château Léoville Las Cases 1986, which I tasted not too long ago, the Mouton Rothschild, tasted earlier this month, exuded initial aromas of intense graphite and pencil lead. It had been opened four hours before but – like Las Cases – proved reserved on the palate, with alcohol at 12.5. Time in glass revealed subtle intensity with fresh fruit and spice underneath, burgeoning freshness and brightness. And what tannic finesse! It was not as tightly wound after over one hour of sipping, but remained very youthful. Then came some fresh meadow and cut herb aspects.

Legend in the making

Château Mouton Rothschild 1986 is truly palate enveloping, or even permeating. It then leaves a long, impressive finish. A wine of power and finesse. More cool blue than ripe black fruit, even though the wine has darker fruit. At nearly 40 years of age, it can be enjoyed in 2025, but needs time and air. I would advise another five to 10 years cellaring to loosen up more, and to acquire more tertiary aspects. Still, what an amazing treat! (99 points)

About the Château

The estate itself, though not originally included in the now famous 1855 classification of wines of the Médoc and Sauternes, was promoted from second to first growth after successful lobbying by then owner Baron Philippe de Rothschild (1902-1988), who had taken a series of long, careful steps to prove the wine worthy of such a promotion. In 1924, he decided that all wines should be bottled at the château, which at that time was not common practice. That decision meant more storage space – and more control over wine quality. The 100-meter long cellar space proved to be remarkably aesthetic, reflecting attention to detail and to beauty. Each year, from 1945, the label of each vintage was illustrated with the reproduction of an original artwork specially created for the wine by a contemporary artist, another practice that sets this wine apart. In 1962, the château itself was transformed into one of Bordeaux’s leading tourist attractions with the inauguration of its Museum of Fine Art, always worth a visit.

Beyond aesthetics, the estate proved in many years how it could compete with illustrious first growth Pauillac neighbors Latour and Lafite. Promotion from second to first growth (a rare change in the otherwise immutable ranking) finally came in 1973, when then French Agriculture Minister Jacques Chirac signed a decree making it so.

The 1986 vintage label boasts an intriguing trio of masks by Bernard Séjourné (1947-1994). The artist was born in Haiti where his family were planters. The white masks on a black background convey mystery and sophistication, interestingly reflecting the style of the wine. You can see all other Mouton labels since 1945, famous for the V for victory, here.

Barrel aging at Château Mouton Rothschild, photo copyright Alain Benoit

Nearly four decades on, the 1986 Mouton Rothschild remains a monument to patience — a wine that reveals itself more in whispers than proclamations. Born of a vintage that rewarded patience, it continues to evolve with slow majesty — firm, fresh, and remarkably youthful. Today, its brilliance lies not in opulence (like the 1982) but in precision — graphite, herb, and cool blue fruit etched against a backbone of iron. Like the château’s own journey from second to first growth, its greatness was never instant but earned through time, discipline, and vision. In a social media driven world, where immediacy is prized, the 1986 reminds us that true greatness often takes its time: It is a legend in the making.

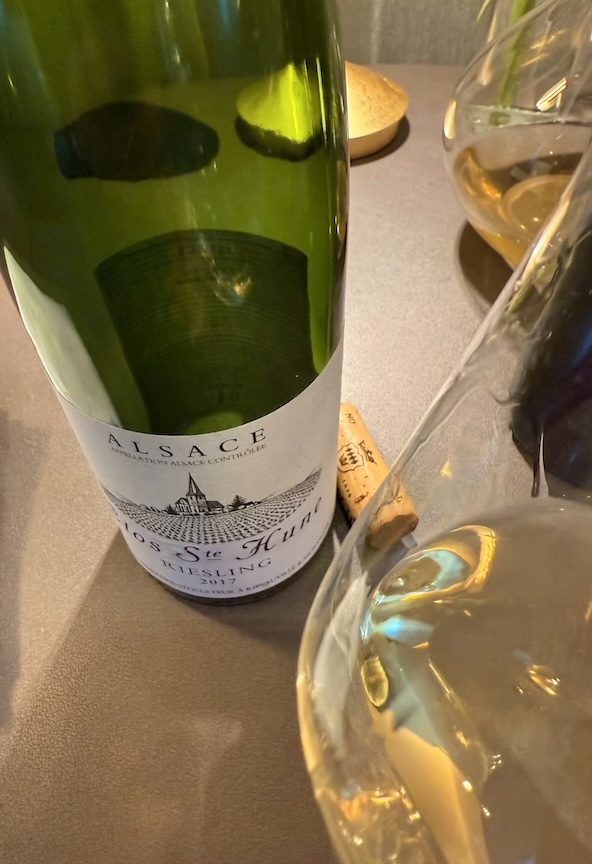

A Star, a Steal… and a Splurge: Lunch with Clos Sainte Hune

Posted on October 16, 2025

Because sometimes “economical” ends at the wine list

A wide variety of cheeses : €15 extra

Although far too young at but eight years since the harvest, time in glass revealed the greatness of Clos Sainte Hune.

Don, Pam, myself and Jürgen

Médoc Blanc officially born

Posted on October 14, 2025

The red stronghold has a white awakening — Bordeaux’s Médoc embraces a lighter side.

By Panos Kakaviatos for Wine Chronicles

14 October 2025

Last year, I wrote in Decanter of prospects for an official Médoc Blanc appellation. That consideration is now reality.

Starting with the 2025 vintage, winegrowers from all eight Médoc AOCs, including Margaux, Pauillac, Saint-Estèphe and Saint Julien, will be able to jointly produce wine under the Médoc Blanc moniker: “A small revolution”, according to a press release issued today by the Médoc, Haut-Médoc and Listrac-Médoc Wine Council, for an appellation previously reserved for red wines since its creation in 1936. Until this year, then, all white Médoc wines are identified as basic Bordeaux appellation wines.

Desired by an increasing number of winegrowers at châteaux across the Médoc, the Médoc Blanc appellation is both “recognition of a little-known tradition and a distinctive product, providing a strong guarantee of quality and authenticity,” so goes the press release.

The lofty words match some reality. Tasting Médoc’s whites can reveal stylistic and price diversity, as producers respond to rising consumer demand for lighter wines. Take for example merchants and enologists in Strasbourg, France. They professed elation over the “surprising freshness” of many white wines from the Médoc. “I was expecting oaky wines, coming from Bordeaux,” said Sylvain Girard who had hosted a tasting at his Strasbourg wine boutique Cave à Terroirs. Like so many autumn mushrooms, white wines have been popping up at rapid rate in the Médoc, and they are not oaky, but often fresh and zingy.

For Claude Gaudin, president of the Médoc, Haut-Médoc and Listrac-Médoc Wine Council, the official recognition of the region’s white wines is “not only a testament to the work of several generations of winemakers from across the Médoc peninsula, but also a burst of optimism for the future.” Referring to market interest for white, he adds that the white wines of the Médoc constitute a “new gateway to discovering (or rediscovering) the magnificent and wide range of our red wines.”

One of my favorite white wines from the Médoc, the Caillou Blanc of Château Talbot, in Saint-Julien (photo courtesy of Château Talbot)

Why Médoc Blanc?

The most well-known Bordeaux whites come from the classified Graves region – specifically from the 1987-created appellation Pessac-Léognan within Graves. Which avid Bordeaux wine drinker does not get excited when hearing the name Haut Brion, for white as well as red? Given the prominence of Pessac-Léognan, industry observers have been dubious about Médoc Blanc.

“A well-behaved Médoc must always be red,” Washington D.C.-based wine educator and former Washington Post wine columnist Ben Giliberti had told me. “Not a single white wine was included in the 1855 classification of the Médoc, and over the centuries, the word claret has become synonymous with Médoc: well-balanced, well structured, and red,” he explained. “For as long as Graves continues to exist, white Médocs are the answer to a question that nobody asked.”

But backers of Médoc Blanc point to a longer-than-expected history of white production there, reaching back to the 18th century. First Growth Château Margaux was making white wine in that century, says director Philippe Bascaules, even if the famous Blanc Pavillon Blanc brand was established in 1920. Château Loudenne, in Saint-Yzans-de-Médoc, bills itself as the oldest consecutive producer of dry whites, with annual production starting in 1880.

That history, once nearly forgotten, is now being written anew. Today, white Médoc has made a confident return, and when I attend tastings in the region, I increasingly look forward to discovering estate whites — many of them remarkably good, from Talbot and Lagrange to Cos d’Estournel and Le Merle Blanc of Château Clarke, a favorite of mine for its excellent price-to-quality ratio.

So, cheers to Médoc Blanc — proof that even in Bordeaux’s reddest heart, there’s room for a white wine magic. 🥂✨

Legend bottled: Château d’Yquem 1967

Posted on October 13, 2025

By Panos Kakaviatos for Wine Chronicles

13 October 2025

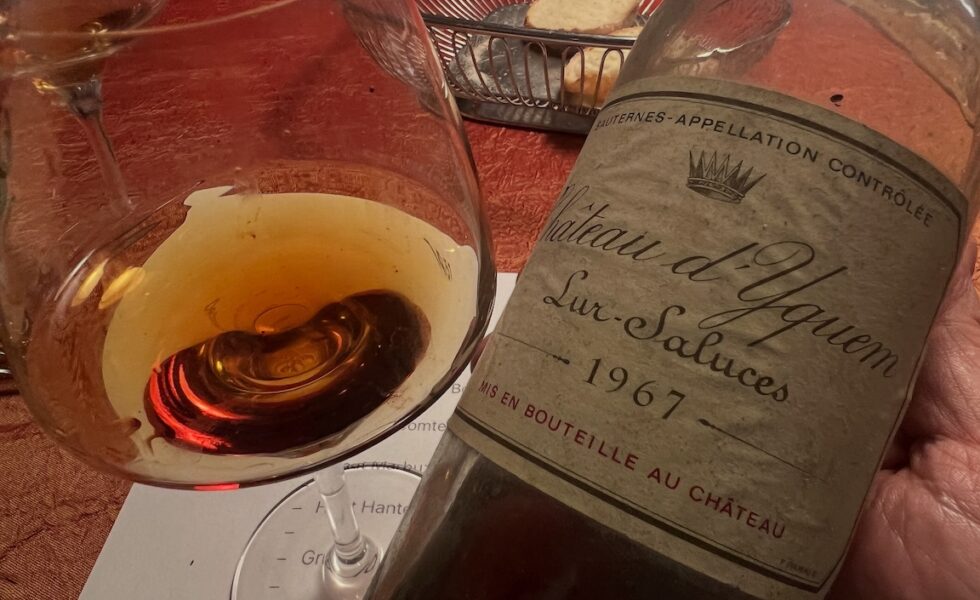

Over a recent dinner with wine pals in Strasbourg, we enjoyed older vintages, some better than others. Château Mouton Rothschild 1986 was stupendous, and I loved Château Ducru Beaucaillou 1986, happily sans TCA: From 1986 to the early 1990s, the estate had some TCA problems, so we were lucky. Two wines stood out as over-performers: Château Haut Marbuzet 1975 and Château Rieussec 1980. And the fascinating label of the Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande 1945 vintage, a bottle that had seen its better days, but was remarkably alive for its 80 years of age, included the incorrect appellation of Saint Julien!

For tasting notes on these and other bottles: go here.

But what about a truly special bottle? A gem that more than meets expectations while fulfilling all “great wine” criteria? In terms of point scores, a 100 out of 100? The meal ended with just that: Château d’Yquem 1967, which I last tasted back at the estate in Bordeaux in 2005.

Dinner on 19 June, 2005 at Château d’Yquem: The Conseil des Grands Crus Classés en 1855 co-organized an exceptional celebration to mark the 150th anniversary of the classification of wines from the Médoc … and Sauternes.

Château d’Yquem reigns above Sauternes, both literally and figuratively. Its vineyards crown the highest point of the appellation, ideally positioned near the Ciron River, whose autumn mists rise at dawn, enveloping the vines before dispersing under the late-morning sun. This fog and warmth interplay nurtures Botrytis cinerea, the “noble rot” that penetrates grape skins through their stomata, gently shriveling the berries, concentrating sugars and acids: transforming ordinary juice into an elixir of amazing depth.

And this natural phenomenon occurs nowhere more consistently than at Yquem. The estate’s slopes, exposure, and drainage combine to produce fruit of astonishing purity and complexity. It is no coincidence that all of Sauternes’ finest estates — eleven first growths and twelve seconds — cluster around Yquem, the only Premier Cru Supérieur, a title that enshrines its unique micro climate and precision of harvest.

In the middle, ideal cheeses for Sauternes: Stilton, Fourme d’Ambert and Roquefort. But also goat cheese and Comte.

About 1967

The 1967 vintage was not easy. While July and August were hot and dry, most of September proved cold and damp, spreading rot – with the ensuing October harvest plagued by intermittent rain. For reds, only top wines succeeded, with most others now forgotten. But as can happen in vintages, what was difficult for reds was better for whites — and vice versa. The wet September promoted botrytis weather, noble rot for Sauternes. But it was not good for all Sauternes either, because selection in the harvest proved essential, as the wet period also led to damaging black rot. The harvest at Yquem lasted from 29 September to 7 November, the repeated “passes” or “tries”— meticulous hand-picking of individual grapes at peak concentration — yielded extraordinary balance between richness and freshness.

Tasting notes for the Yquem 1967 in 2025

The host of our dinner, Jean Haudy, had interned at Château d’Yquem in the 1980s when staff said that the 1967 was vintage “of the century” material. The wines when young, it was said, conveyed layers of ripe apricot, saffron, honey, and candied orange peel, yet sustained by a spine of vibrant acidity that has carried them effortlessly through the decades and to our dinner in 2025, 58 years later.

How is the wine today? I could tell just from the aromas that it was special. Not just the complexity of cinnamon, crème brûlée, toffee, orange marmalade and dry apricot, but also from the aromatic texture: I could sense a power in the aromatic profile that came through on the palate. So much structure, it felt like red wine tannin. But then the delectable combination of botrytis-derived spice, tertiary and primary fruit flavors, including spicy pineapple, dry herb and beeswax, led to a palate enveloping sensation and long finish. Complex yet youthfully powerful, for a wine nearly 60 years old. One could almost say that the wine is still a baby, if not a mid-30s adult: not bad for a wine nearly 60.

When I last tasted the 1967, some 20 years ago, the wine fetched up to $2,000 a bottle. These days, the price is closer to double that amount. Even in an era when Sauternes is out of fashion – as mentioned in my article for Wine Review Online – Yquem maintains strong demand.

Older vintages dinner, the best for last

The estate’s large size makes it possible to plant 113 hectares of vines on a very representative sampling of the rich tapestry of the Sauternes region’s soil types. This extraordinary variety of soils is another key factor in the quality and complexity of Château d’Yquem. Indeed, two to three hectares of vines that are too old are uprooted annually, and the soil left fallow for a year. Furthermore, it takes at least five years before new vines produce grapes that are up to Yquem’s very strict standards. Twelve hectares of vines are thus non-productive every year. Yquem is planted with two grape varieties: Sémillon (75%), which produces a rich wine with body and structure, and Sauvignon Blanc (25%), an early-ripening but less reliable producer, which contributes aromas and finesse.

The fact that all of Sauternes’ great growths (eleven first growths and twelve seconds) are located around Château d’Yquem – the only Premier Cru Supérieur – tends to bear out Yquem’s ideal location. The magic phenomenon of botrytisation is nevertheless fragile and subject to numerous meteorological factors.

In posting notes about this wine on the popular wine forum Wine Berserkers, several forum members agreed with Yquem 1967’s legendary status. Indeed, one posted a reply, as follows: “I’ve had the ‘67 Yquem twice and it defied scoring. Magnificent, each bottle unique and soul-stirring. Among my top all time as well.” Indeed, 100 points doesn’t quite do the wine justice.

Wine is to alcohol what Beethoven is to noise

Posted on September 24, 2025

Why wine is not the same as cigarettes, vodka or Coca-Cola: An appeal from the International Wine Academy (AIV)

24 September, 2025

This week at the 4ᵗʰ United Nations High-Level Meeting on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases and the promotion of mental health and well-being, the wine world faces a challenge: How to prevent and control noncommunicable diseases without making culture collateral damage on the altar of public health?”

When most people think of the UN General Assembly, Ukraine, Gaza and other pressing geopolitical issues come to mind. But wine, via the UN’s World Health Organization (WHO), is a major part of the UN brief.

One can argue that the wine industry has not done enough to stress the potential ill effects of alcohol in wine, but it is absurd to reduce wine to just alcohol. And yet that is what the World Health Organization’s “Zero Draft Political Declaration” does. Still under review, it proposes further taxing wine as tobacco, spirits, or sugary drinks. Wine is neither Coca-Cola—nor cigarettes. Especially putting wine at the level of evidently harmful tobacco consumption is disingenuous.

While tobacco has zero redeeming qualities, wine – in moderation – does. Take for example a 2022 NIH study – among many others. While the alcohol abuse, including wine, is seriously harmful to health, the study points to epidemiological and clinical evidence on the protective role of moderate quantities of wine on health. In differentiating wine from more harmful hard alcohols, like vodka, the study notes that a moderate intake of wine was associated with a significant reduction in cardiovascular events including cardiovascular death.

And yet the WHO draft calls for reducing the “harmful use of alcohol” by:

1. Banning or comprehensively restricting exposure to wine advertising

2. Restricting the physical availability of retailed wine

3. Enacting and enforcing drink-driving laws

The last point makes sense. But lumping wine with all liquor under the first two is misguided.

Provisions from the WHO Global Alcohol Action Plan 2022-2030 (GAAP) seek a 20% reduction in per-capita alcohol consumption by 2030 (from a 2010 baseline). The plan aims for 70% of countries to have introduced, enacted, or maintained key “high-impact policy measures” by 2030, which target pricing, availability, and marketing of alcohol.

How denormalizing wine could “destroy a heritage”

The World Health Organization (WHO) and UN agencies moreover talk of “denormalizing” alcohol, which means changing public attitudes so that drinking wine is no longer seen as normal, socially acceptable behavior, and reducing cultural acceptance of alcohol in public life (advertising, sponsorships, social events, etc.). Denormalizing also discourages associations between wine and positive values like celebration, success, or relaxation while framing wine like tobacco: something inherently harmful that should not be promoted, normalized, or glamorized in society.

In its Appeal to the UN (also in French), the Academy of Wine (AIV) points out that wine is more than a drink: it is history, heritage, culture – and economy. Indeed, with tariffs already straining exports, equating wine with spirits risks economic loss.

From the Appeal:

TO DENORMALISE WINE WOULD DESTROY A HERITAGE – A LEGACY OF HUMANITY

Wine embodies eight millennia of human history: it is a catalyst for conviviality, joy and sharing; a connection to the land and its landscapes; a universal language linking people – from Georgia to Ancient Greece, from Oregon to Tuscany, from France to New Zealand. Unique yet global, it expresses mankind’s patience before time, humility before the earth, and the desire to celebrate together. Offering a glass of wine is a gesture that expresses peace, friendship, brotherhood, and the joy of being together.

On the joy of being together, with wine

Enjoying wine moderately is to defend the culture of taste and restraint, and perpetuate a bond that unites continents, people and generations. It is about appreciating rather than abusing, tasting rather than drinking. It is about approaching health through social and family ties, mental well-being and the joy of life – for the link between happiness and health is undeniable.

Wine also concerns diplomacy. This past July in Strasbourg, French Ambassador Pap Ndiaye hosted Council of Europe a Bastille Day party with fine Bordeaux from Pessac-Léognan. The title image for this article comes from the fête, showing Pessac-Léognan winemakers Ghislain Boutemy, at left, and Jacques Lurton, who is President of the Pessac-Léognan Wine Council. As ambassadors and other staff from the 46 member states of the Council of Europe were exchanging ideas about pressing issues in private conversation, they enjoyed fine red and white wine brought from Pessac-Léognan to Strasbourg. Guests discovered some history from the Graves region, where the appellation Pessac-Léognan exists, including Samuel Pepys’ 1660s praise for Ho-Bryan—the future Château Haut-Brion. One of countless examples proving that wine is far more than “alcohol.”

As I wrote in Politics, Wine and Diplomacy for Jane Anson, many political decisions happen not in press-covered official gatherings but over private dinners infused with wine. Why wine, and not heavier alcohol? Because wine encourages both conversation and reflection. As Churchill said of Champagne: “the wine of civilization and the oil of government.” Hemingway added: “Wine is one of the most civilized things in the world… offering a greater range for enjoyment and appreciation than, possibly, any other purely sensory thing.”

So when UN member state delegates consider this WHO/UN draft over dinner with fine wine, they should take all of the above into account before approving it. Wine is heritage. Wine is culture. Wine is diplomacy. To reduce it to a health risk alone would be to deface a cornerstone of civilization.

Wine Chronicles

Wine Chronicles

Recent Comments